Great article in PDN about yours truly, written by writer Dzana Tsomondo. Thanks PDN!

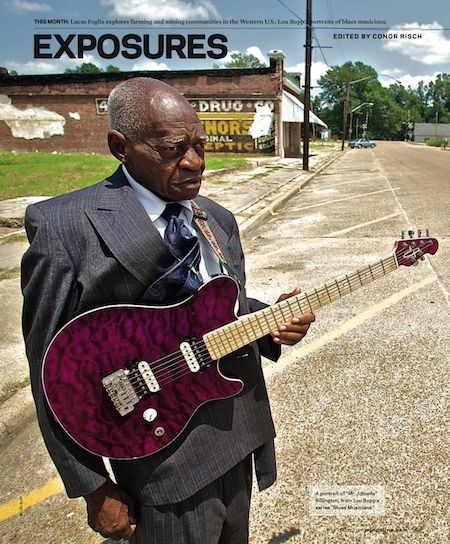

THIS MONTH: Lou Bopp’s portraits of blues musicians.

PRESERVATION

A personal project documenting blues musicians helped commercial photographer Lou Bopp land exhibitions and rediscover the passions that brought him to photography.

BY DZANA TSOMONDO

THE MAN SMILES broadly, revealing several missing teeth, as he holds his callused and bandaged hands up to the camera, palms out. They are the tools of a blues musician and, even without a guitar, they tell one hell of a story. “Portraits of the Blues” by Lou Bopp is a fascinating visual compendium depicting—through portraits, landscapes and details—a fading culture and the musicians who helped build it, with their hands and guitars.

Bopp is a commercial photographer whose client list is packed with heavyweights like Time Warner, Sports Illustrated and American Express. He has worked all over the world, once shooting on three continents in a single day, but it wasn’t an assignment that brought him to rural

Mississippi, the birthplace of blues, it was his own love of the music. For Bopp, this project is first an act of documentation. He is keenly aware that the sun is setting on these aging musicians and with them, a golden era in American culture and music. “There are not a lot of young bluesmen in the pipeline unfortunately,” Bopp notes. “I have photographed 70 to 80 musicians and about half have already passed.”

Bopp credits his own curiosity for much of his success as a photographer; it’s also what inspired “Portraits of the Blues,” which is currently showing at August House Studio in Chicago. Bopp grew up a fan of artists like Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix. As he explored their influences, he found they invariably led back to the blues. Bopp became a fan of the music and years later that same investigative urge spurred him to ride his motorcycle down Route 61 from his home in Missouri to Clarksdale, Mississippi, a historic blues hotbed. What was intended to be a daytrip stretched into three or four days of roaming the Delta, searching for the music. That first spur-of-the-moment trip yielded photographs of legends Big George Brock and Robert “Wolfman” Belfour, along with an invaluable resource in Roger Stolle, a writer, artist and owner of Cat Head Delta Blues & Folk Art, a store in Clarksdale.

Connections proved invaluable to Bopp, as actually finding the musicians was and is the most difficult part of the project. Using an ever-expanding network of like minds and employing the occasional local fixer, Bopp found his way to the music, even if it meant being a long way from paved road. He makes it clear that a willingness to compensate his subjects went a long way; after all, some of the artists had made a good living playing the blues, but most hadn’t, regardless of their place in the canon. “I paid honorariums to everyone I shot,” he says. “Their time is valuable, my time is valuable. I respect people’s time.”

No matter his commercial workload, Bopp always makes time for personal projects. He credits his years spent working on the blues project in Mississippi with allowing him to “get back to the roots” of his love for photography. A penchant for travel and culture are what brought him to the art form, and that is what drove him back to Clarksdale, time and time again.

Bopp decided early on that he wanted to shoot the artists in their element, but not onstage. “I wanted to shoot them behind the scenes, at their homes,” Bopp explains. “One guy, Pat Thomas, I shot him at his father’s graveside. I wanted to get a little deeper and peel away the layer of their public persona.” His aim was to pull back the curtain, as it were, and capture something more intimate.

His photographs of Wesley “Junebug” Jefferson are a particularly poignant example. Roger Stolle put Bopp in touch with the obscure-but-legendary Delta bluesman, and though he was ailing, Jefferson invited the photographer to his home. The bedridden musician insisted on being photographed with his guitar and, unnerved but profoundly honored, Bopp obliged. Jefferson passed away only days later.

Unlike his commercial assignments with their attendant crews, production meetings and top-down creative direction, “Portraits of the Blues” has been a lean operation. Bopp works alone, traveling light and following his own compass. That challenge—and freedom—is part of why he finds the entire experience of pursuing his own projects so rewarding. He relies heavily on natural light, which he finds in abundance in the South. “The patina is beautiful, its got tons of character,” Bopp says. “Some guys got dressed up for me and some didn’t, I tried not to dictate things.”

Balancing the demands of his commercial work and “Portraits of the Blues” was a bit of a “juggling act,” but Bopp is proud to have never canceled any appointments—not with his ad clients and not in Mississippi. Structurally, his approach to shooting the images remained the same: get the “meat and potatoes” first. In one world that meant shooting the creative brief before trying to do it his way. In Mississippi it meant “think fast,” and make sure you get a shot you can use, all the while leaving “space for serendipitous moments,” he says.

Bopp’s income from his commercial work also allowed him to self-fund “Portraits of the Blues.” Surprisingly, chasing his passion in Mississippi would open the door for more commercial work when his images caught the attention of an agency in Jackson, Mississippi, which contacted him directly. What initially was going to be a simple licensing arrangement ended with Bopp directing four TV spots for the Mississippi Tourism Association.